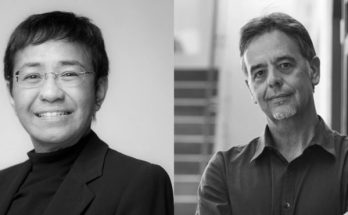

Chris Tenove is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the School of Journalism, Writing, and Media at the University of British Columbia. Together with Peter Klein (Professor of Journalism and Executive Director of the Global Reporting Centre at UBC) and Ahmed Al-Rawi (Assistant Professor of Communication at Simon Fraser University), Dr. Tenove leads “Shooting the Messenger: Credibility Attacks Against Journalists,” a research project funded by Mitacs and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Chris Tenove is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the School of Journalism, Writing, and Media at the University of British Columbia. Together with Peter Klein (Professor of Journalism and Executive Director of the Global Reporting Centre at UBC) and Ahmed Al-Rawi (Assistant Professor of Communication at Simon Fraser University), Dr. Tenove leads “Shooting the Messenger: Credibility Attacks Against Journalists,” a research project funded by Mitacs and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

PEN Canada: Why is the Global Reporting Centre studying journalists who are targeted by campaigns of disinformation and harassment?

Chris Tenove: Our project is called “Shooting the Messenger,” and we are looking at efforts to threaten, discredit, harass, and otherwise undermine journalists globally when they are trying to do their jobs. We are working on this project with PEN Canada and with the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). For years, CPJ has been tracking murders, disappearances, and jailings of journalists. Those blunt tactics continue, but they are now complemented by information campaigns against journalists. These might include spreading false claims about journalists or news outlets, making anonymous threats, or exposing private information about journalists and their family members, and these tactics are often paired with surveillance. Prominent journalists targeted in this way include Rana Ayyub in India, Ronan Farrow in the US, and Maria Ressa in the Philippines..

We might think of these organized efforts to undermine journalists as “top-down” campaigns. Journalists globally also seem to be facing rising levels of “bottom-up” hostility and harassment from the public. Top-down and bottom-up attacks are often related. For instance, President Trump in the US and President Bolsonaro in Brazil are clear cases of political elites stoking anti-press sentiment and encouraging supporters to lash out at individual journalists. For journalists on the receiving end, a threat, a false accusation, or a series of sexually explicit messages can have negative impacts on their mental health, security, and ability to report, regardless of who it comes from.

PC: How are you going to study these problems?

CT: We will soon launch a global survey to investigate patterns in the harassment and credibility attacks journalists face, the likely sources of those attacks, and their impacts. We will compare the experiences of journalists in more or less democratic countries, and examine how journalists’ gender, ethnicity, religion, and other factors may shape their experiences. We are also doing some social media investigations, working with partner organizations to look at information campaigns against journalists in a few countries.

The Global Reporting Centre focuses on solutions to the problems that journalists face, so we will be working with partners like PEN Canada to provide recommendations and resources for journalists .

PC: Isn’t this mainly a foreign problem? How does it affect Canada?

CT: Canadian journalists tend to have thick skins, but they face increasing abuse and harassment. A recent IPSOS survey of Canadian journalists found that 72% had experienced harassment, such as violent threats and sexualized messages, in the last year. The survey came out not long after Maxime Bernier, leader of the People’s Party of Canada, called on Twitter for his supporters to “play dirty” with journalists. The Coalition for Women in Journalism found that at least 18 women journalists received vile and threatening emails following his remarks. (Twitter briefly suspended Bernier’s account.) In a rare show of unity, many news organizations came together to publicly declare that “there can be no tolerance for hate and harassment of journalists or for incitement of attacks on journalists doing their jobs,” and observed that such attacks “inordinately target women and racialized journalists.”

So, unfortunately, Canadian journalists do indeed face these issues.

PC: How can we distinguish deliberately misleading and harmful content from genuine dissent or passionate disagreement? Is this just in the eye of the beholder? Or, put another way, could efforts to crack down on harassment and credibility attacks also reduce freedom of expression?

CT: In my research, I’ve seen messages to journalists that are unambiguously hateful or threatening. We already have criminal provisions against communication like this in Canada, though enforcing these laws can be difficult. Messages like these are clear efforts to reduce the freedom of expression of other people.

However, there is a lot of communication in the “lawful but awful” category, which would include most insults and false claims that journalists face. I’ve examined thousands of tweets at journalists as part of research I’m conducting with Elizabeth Dubois of the University of Ottawa, and these insults or misrepresentations do not strike me as genuine attempts to advance a challenging point of view. That doesn’t mean people should be banned from a social media platform or charged with a crime for such remarks. However, journalists shouldn’t have to see or respond to such remarks, either, if they would prefer not to.

Social media platforms and news media companies need to get better at helping journalists manage the toxicity they face. That’s particularly true for women and racialized journalists, who are more likely to be attacked online for who they are rather than what they say. There are many good recommendations for helping journalists manage these issues. For a particularly thorough look at those options, see the No Excuse for Abuse report by PEN America.

PC: These concerns about toxicity or hate online are problems that go beyond journalism. The federal government has been proposing measures to address these problems. Where do you think those efforts will take us?

CT: You’re right, journalists aren’t alone. I’ve previously investigated the extensive abuse faced by Canadian politicians, for instance. Others have looked at online misogyny and racism in Canada. In response, the Liberal government promised legislation to create a new regulatory framework to address specific forms of harmful content, including hate speech, terrorism, and child sexual exploitation. I support the creation of a new regulatory body for this issue, but the proposed framework has some flaws, including very troubling enforcement powers.

There are important and complex debates to be had about how to improve the digital media environment and minimize the harms it facilitates. I worry that when the Liberal government puts forward their legislation, the public discussion will be unhelpfully politicized and dumbed down. Hopefully, good journalism will help Canadians understand and weigh in on the issue.

PC: In the meantime, what do we do about efforts to discredit and delegitimize journalism, including efforts by politicians and other influential actors? How can we support the journalists who face threats and harassment online?

CT: That’s tough because these challenges are not going to end any time soon. Journalism organizations need to step up and provide resources and assistance to journalists, particularly those who face disproportionate burdens. This needs to be addressed as a workplace safety and equity issue. I think the industry needs to shift from recognizing that fact to finding practical solutions.

At the same time, journalists can’t address this on their own. Social media users can step in as active bystanders when they see journalists unfairly attacked, and boost what they believe to be high-quality reporting. Above all, journalists need engaged supporters who will reward them for being trustworthy information sources and convenors of public discussions, and criticize them — civilly, please! — when they fall short.

—–

Chris Tenove is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the School of Journalism, Writing, and Media and the Department of Political Science, University of British Columbia (UBC). He has published peer-reviewed articles, book chapters, and policy reports on topics such as disinformation, harmful speech, cyber-security threats, and social media regulation. He previously worked as a journalist, and contributed to The Globe and Mail, National Post, Maclean’s, The Tyee, The Walrus, This American Life, CBC Ideas and other publications and radio programs. He is conducting research with the Global Reporting Centre, an independent news organization based at the University of British Columbia.