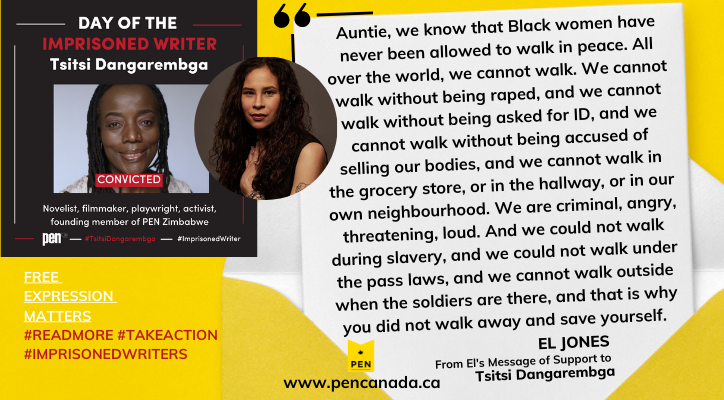

Dear Auntie Tsitsi,

You told us that the problem was not us, that the sickness was colonialism. You showed us a way to be at home.

You could not be ignored. You diagnosed them to their faces, and they had to praise you for it. You could have become their head girl then, petted, paraded around, the symbol of what Africans could become while Zimbabwe became a memory for you, a slight spicy flavour, a colourful thread. The whole world was in front of you then, and you chose to stay. You did not want to be the only, the Black face in the white room, the exceptional. You were calling all of us along with you, and lifting up so many to come.

And you were already moving forward, making films, advocating for those dying from AIDS and left in its ruins, and always fighting for women. Where is her next book? everyone asked, trying to consume you. You did not write to our command. And you did not leave the place, Zimbabwe, where your life and work was, not even as you struggled to find the space and the resources to write.

Do you know, Auntie, how much that meant to us? I am not in Zimbabwe. I am here in Canada, where I can (I think) walk around with a sign and not be arrested, but where we still do not have room to write. In Black and Female, you write about being a Black woman under empire, in a world that does not love us, that does not hand us opportunities, that will praise us and take from us and still not ensure that we can live, let alone write. And you showed us that, regardless, we do not have to compromise ourselves or give ourselves away. And when the universities and the publishers and agents rejected me, there you were walking with a sign in front of me, like so many of our Black foremothers, saying, no – this is the right way. Keep walking. Don’t turn back. Live as you must, and write from there.

You were walking with a sign in front of me, like so many of our Black foremothers, saying, no – this is the right way. Keep walking. Don’t turn back. Live as you must, and write from there.

Auntie, we know that Black women have never been allowed to walk in peace. All over the world, we cannot walk. We cannot walk without being raped, and we cannot walk without being asked for ID, and we cannot walk without being accused of selling our bodies, and we cannot walk in the grocery store, or in the hallway, or in our own neighbourhood. We are criminal, angry, threatening, loud. And we could not walk during slavery, and we could not walk under the pass laws, and we cannot walk outside when the soldiers are there, and that is why you did not walk away and save yourself.

You have never compromised. You never chose writing over life, over freedom. You never let yourself be compressed. And Auntie, we already know they will not break you or any other women. We see the women in Iran, and we know that when men get their power from controlling women, they have no power at all. This is all they have, their police and their courts and their threats and they do arrest us, and they do torture us, and they do kill us and yet – and yet they cannot stop mouths and pens and raised fists. And they cannot stop love, and solidarity. They have all the instruments of power and yet they are so weak and scared.

Thank you for writing us, and for not leaving, and for not stopping. Thank you, Auntie, for your risks, which I know were not risks at all for you, but simply necessities for living.

Auntie, thank you. Thank you for writing us, and for not leaving, and for not stopping. Thank you, Auntie, for your risks, which I know were not risks at all for you, but simply necessities for living. You never had to do more for us, but you did. And no arrest, no threat of prison sentence, no patriarchal power, none of that can hold you, or contain you, or shut you up. And Auntie, because you are, they have already lost.

With deep love and gratitude,

El Jones

El Jones is a poet, journalist, professor and activist living in Nova Scotia, Canada. In 2016, she was awarded the Burnley “Rocky” Jones Human Rights award by the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission for her advocacy on prisoners’ rights. El is an assistant professor in the Department of Political and Canadian Studies at Mount Saint Vincent University, where she previously served as the Nancy’s Chair in Women’s Studies. Her book Abolitionist Intimacies was released in November by Fernwood Press.