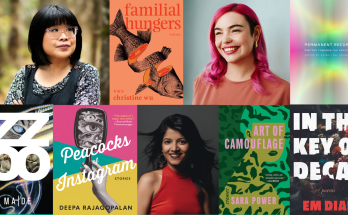

Deepa Rajagopalan is completing her MFA in Creative Writing at the University of Guelph, and is a graduate of the Creative Writing program from the University of Toronto. She is an editor of Held magazine, and is the co-host and curator of the Emerging Writers Reading Series in Toronto. She is working on her first book, a collection of short fiction. She currently lives in Guelph, Ontario.

PEN Canada: As a curator of the Emerging Writers Series and as an MFA candidate at Guelph, what does it feel like to have your work recognised by a jury and an award like this?

Deepa Rajagopalan: The journey to publication for an emerging writer often feels insurmountable. To be recognized by PEN Canada, especially coming from this jury, is such an incredible honour. It brings validation, and much-needed encouragement. As an organization that supports refugees, and advocates for the right to freedom of expression, PEN Canada is doing such important work in today’s climate. In addition to being paid for your work, the opportunity to work with a mentor is invaluable.

PC: The New Yorker archivist, Erin Overbey recently published data about the lack of diversity in the magazine’s bylines. In 96 years the print version of the magazine has published only 4 book reviews by African-American women; in the last 30 years only 7 reviews by Latino writers and 12 by Asian-Americans have appeared, and less than 1 percent of the total are by Indian-Americans. In your experience, do Canadian writers face similar barriers? If so, what could be done to address this?

DR: Overbey’s data was sobering, but not entirely shocking. In answering this question, I think it is useful to think of another question: Who gets to be called a “Canadian” writer, unhyphenated? While more diverse voices are being heard now, the stats are still heavily skewed. A disproportionately large number of underrepresented writers, including Indigenous, Black, racialized, LGBTQ2+, disabled writers, continue to face barriers in entering the literary scene.

Acknowledging that we are operating from a colonial context would be a step in the right direction. As Overbey suggests, mastheads at prestigious publications need to start looking different. Re-evaluating what gets to be called “good” literature, what is coherent and what isn’t, is necessary. This would result in better, richer “content”, which is ultimately good for everyone.

The University of Guelph offers a workshop taught by author Carrianne Leung called Writing the Decolonial Fiction. Such a workshop should be essential learning for all of us, writers and publishers, because it gives us language to talk about these things, and challenges the status quo.

At the Emerging Writers Reading Series, we try to ensure that at least 60% of our readers are from underrepresented communities. As opposed to thinking of representation as checking off a box, I like to think of it as highlighting stories and voices that we haven’t seen before.

PC: Many argue that our increasingly post-literate culture fosters populism and may be producing a “re-tribalization” of society. Do you agree? What role might creative writing play in resisting this tendency? Which writers do you think have done so most effectively?

DR: Populism in our post-literate culture is amplified because of this increasingly binary way of thinking. The lack of dialogue and nuance is frustrating. Writers resist this tendency by supplying the nuance, sometimes as the quiet voice of reason that helps reach across aisles, and sometimes with the fervent rage needed to make a point.

In an interview with The Paris Review this year, Arundhati Roy said she feels uncomfortable being described as a “writer-activist” and likened it to the term “sofa-bed.” She doesn’t consider herself an activist at all. Roy’s work, both fiction and her essays, has been suffused with this obsession with understanding how to think about power, and keenly resisting populism.

PC: Which writers would you like most of your generation to have read? Why?

DR: Oh, this is so difficult. I’ll try to keep it short. Arundhati Roy, especially her novel, “The God of Small Things,” for what she does with language, and her pointed irreverence. Kazuo Ishiguro, for his deceiving simplicity, and the haunting characters, and worlds that they inhabit. Alice Munro, for her subtle brilliance, and the art of surprise. Toni Morrison, for her precision and emotional profundity. Gabriel Garcia Marquez, well, for being Marquez.

PC: You have lived in four countries (India, Saudi Arabia, the USA and Canada). How has the interplay of these experiences influenced your writing?

DR: I come from the state of Kerala in India. I was born in Saudi Arabia though, where my parents were working at the time. It was a common thing, this economic migration, despite having to live in a restricted country like Saudi Arabia. At the age of twelve, I moved to a boarding school in Kerala. As a young adult, I moved to the USA, and later Canada.

The vantage point from where I view the world is somewhat fluid. There is a lack of groundedness, which can be disorienting at times, but also liberating. I like to joke that I feel at home nowhere and everywhere. There is a sense of tingling possibility, at all times. There is also a sense of unabating loneliness. When I write, I am drawn to characters who have a fluid sense of home. Many of them don’t have the luxury to think of things like belonging and are just trying to get by, either financially or emotionally. A lot of writing is about keen observation, and I think it comes with the territory of being the outsider.

PC: What are you currently reading? What books have you found most helpful during the Covid lockdowns?

DR: I am currently reading Shuggie Bain, by Douglas Stuart. Reading, and writing have held me closely during the pandemic. So many books. A lot of Alice Munro, Jhumpa Lahiri, Zadie Smith. Avni Doshi’s “Burnt Sugar.” Kazuo Ishiguro’s “Klara and the Sun.” Souvankham Thammavongsa’s “How to Pronounce Knife” is one book I have read many times in the past year. You can enter the stories from anywhere and they are flawless: every sentence, every word, in place.