The Syrian civil war, which began in 2011, has been a devastating and prolonged conflict led by the Syrian government under Bashar al-Assad. The conflict has caused immense humanitarian suffering, with over 200,000 civilian casualties, including 25,000 children, and millions forced to flee their homes.

On Sunday December 8, 2024, news broke that Assad had fled and the government had fallen, liberating the citizens it stifled for decades.

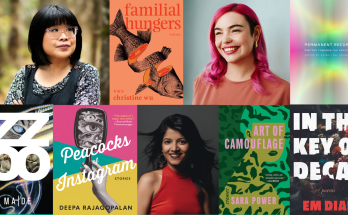

We asked five Syrian and Arab writers living in Canada to reflect on the fall of the regime, and what they hope for Syria.

The Price of Freedom, The Burden of Hope

by Abdulrahman Matar

During the last few days, three scenes did more than capture my attention as a writer and a journalist who covers Syria, they overwhelmed my soul. The first was the opening of prison doors and detention centers to let those who had been forcibly disappeared go free, running in the streets in all directions. The second was of local communities in rebel areas , rising up again, peacefully, to liberate their cities and countryside before the armed opposition forces reached them. As for the third, it was the toppling of all statues of Hafez al-Assad, a profound expression of the end of the Assad era, 55 years of repression, arrests, and physical liquidation under torture in prisons.

Freedom of expression was all but eliminated by the Assad regime; fear controlled everyone. The authorities monitored the press and cultural institutions, subjecting them to constant surveillance, preventing any practice of free thought, or speech. Dozens of Syrian writers, journalists, and civilians, were arrested for their political opinions or their activism for rights, freedoms, and democracy. The regime also assassinated and arrested Lebanese and Palestinian writers, journalists, and activists.

Throughout the past few days, as I have followed the cases of newly liberated detainees, I have felt a great and painful shock as I see the pictures of prisoners who have lost their memory, or are physically or mentally disabled as a result of brutal torture and imprisonment for many years.

I look at myself, and I close my eyes. I am the survivor of Assad’s massacres, the survivor of torture in prisons. I could have been one of those found in dark cells, not knowing who I was. Or my body would have been found, dead, somewhere, like the body of an unidentified prisoner.

Despite my great joy at Assad’s escape, I feel very sad. Tens of thousands of political prisoners and detainees are still missing. Only about 5,000 prisoners have been found or released out of approximately 160,000 detainees whose enforced disappearance has been documented, in addition to 15,000 who were killed under torture. The Assad regime maintained secret and public prisons, and mass graves in places that are still unknown, in order to reap the lives of Syrians for half a century, especially since the uprising in 2011.

Assad has fallen. On the first day, we were so happy that we cried.

On the second day, we cried because of the horror of Assad’s crimes in prisons, while remaining optimistic that the armed opposition forces are committed to protecting civilians and preserving private and public property, a hope that has not yet been disproved.

On the third day, anxiety began creeping into us about the future of Syria. We are looking forward to a democratic civil state. The military leadership of the armed factions, apparently wants to impose its ideology on our diverse and varied society. We fear this, because of their history of repression, arrest, torture, enforced disappearance, and the prevention of freedom of expression in the areas which Jabhat al-Nusra has controlled in northern Syria since it’s founding in 2012.

If Syrians cannot forget the horrific crimes of the Assad regime, then they also cannot forget the crimes of the new military leader today (al-Joulani – Ahmed al-Sharaa). Syrians have offered half a million martyrs, a quarter of a million detainees, and 12 million displaced persons and refugees, for freedom. We do not want, and will never allow, the return of dictatorship to this country. Today, we look forward to peace and justice, first.

Matar is a Syrian Canadian writer and journalist, and the Executive Director of the Syrian Writers Association.

Syria: What comes after Assad’s fall?

by Raffi Minas

December 8 is the day when Syrians ended 54 years of dictatorship—a day that three generations have awaited with hope that never faded. Today, I can finally say that I will go to see my family, home, and city. I can now return without fear of arrest or disappearance. I can now see my stories and books in Syrian libraries and present plays on my country’s stages freely.

I will not talk here about history and how this dark dictatorship began. Instead, let us look to the future, as we always have and always dreamed of. The biggest question today is: what’s next?

This moment may feel like the end—and for the dictator, it is—but for Syria and Syrians, it is just the beginning. Today, we’ve witnessed opposition factions liberating Syrian cities one after another with great popular support and in a peaceful manner, though not without suspicion and caution. This caution is understandable, considering the violations some cities endured under extremist Islamic factions. While these factions opposed the regime, they were also against a civil state, freedoms, and democracy. Our happiness today is indescribable, but we must sober up from the euphoria and seriously consider the future.

For decades, this regime has worked not only in destroying infrastructure but also in breaking the Syrian people psychologically, emotionally, and intellectually. Many pressing questions weigh heavily on our minds.

Will these factions fulfill their promises to establish a secular, democratic authority that represents Syria’s diverse spectrum, or will we face a new dictatorship and the dawn of another revolution?

To what extent are foreign powers committed to refraining from interfering in the processes of defining our identity and building our government and constitution? It is true we have rid ourselves of the Iranian presence and Hezbollah militias, but Russian and American bases remain on Syrian soil. Meanwhile, the Turkish “Sultan” smiles knowingly at the anxieties of Syrians who yearn for a civil government—neither religious nor military.

We haven’t even begun to address the critical need for medical and psychological support for survivors of detention centers. This support must extend not just to them, but also to their families and the refugees still living in camps across neighboring countries, waiting for borders to reopen so they can return home. What about rebuilding the educational, intellectual, and cultural foundations that have completely collapsed!

Documenting the regime’s crimes and building a stable civil society may take three generations or more. We have huge work ahead of us and must proceed with great caution. But I hold a profound faith that the people who succeeded in ending a 54-year-old regime can also resist any new authority that fails to represent the voices of Syrians and their right to freely and democratically determine their future.

Between the Memory of Oppression and the Seeds of Hope

by Basima Tkrory

It is difficult to discuss the repression of post-colonial regimes without referencing the Assad regime’s prisons, especially Sednaya, which has long stood as a harrowing symbol of terror and oppression. Within its walls, humanity and dignity were stripped away across generations. The sheer scale of suffering was enough to challenge comprehension. Yet Sednaya was not the only theatre of horror. For Syrians, the mere thought of falling into the hands of Assad’s shabiha militia, even before reaching these monstrous human slaughterhouses, was enough to turn the lives of detainees, and their families, into an unending nightmare.

Beyond physical repression, this system of terror extended to an all-out war on freedom of expression. Syrian writers, journalists, academics, and students were hunted for their words, opinions, or for publications that dared to challenge the regime’s narrative. Those who sought to articulate an alternative vision for Syria were silenced through imprisonment, torture, or enforced disappearance. Universities became traps, intellectual spaces were gutted; even the mildest criticism was met with the harshest punishments, sending a clear message: no voice was safe from the regime’s grip. In Assad’s Syria, thought itself became a crime punishable by obliteration.

This systematic repression can be analyzed through Antonio Gramsci’s theory of cultural hegemony. According to Gramsci, power does not rely solely on physical coercion but on creating ideological systems that normalize and legitimize oppression. In Syria, Sednaya Prison was not merely a tool for silencing dissent but a mechanism to embed fear into the collective consciousness.

The videos of detainees being forced to proclaim Bashar al-Assad as their “supreme lord” under relentless beatings, dragging, and humiliation are not simply acts of physical or psychological abuse. They embody what Pierre Bourdieu describes as symbolic violence, systematic efforts to obliterate the symbols and values that grant individuals their dignity. In these moments, it is not only the body that is crushed but also the spirit, forced into total submission until it becomes entirely void of resistance. This symbolic violence extended beyond the individual victim, sending a chilling collective message: total submission is the only path to survival.

But this repression did not merely dismantle society through torture and imprisonment. It destroyed the capacity for critical thought and self-liberation on both the individual and collective levels. This leads us to a fundamental question: “What does liberation mean?” Paulo Freire’s theory of liberation asserts that true freedom begins with reclaiming one’s humanity and capacity for critical thinking. In Assad’s Syria, this capacity was systematically crushed. Syrians lived in perpetual fear—not just of speaking out but of questioning or even thinking. Citizens were reduced to beings conditioned to silence and submission, fully subjugated to a regime that aimed to strip them of their very essence.

The horrifying truths of Sednaya and the regime’s other slaughterhouses force a difficult reckoning: liberation is not merely the fall of a regime or the reclamation of land. It is the restoration of humanity, systematically degraded through decades of violence and oppression. The wounds inflicted by this regime are not merely physical but deeply psychological and intellectual. Repairing these wounds, as Gramsci suggests, requires deliberate efforts to rebuild social trust and relationships eroded by years of systemic terror. As Freire reminds us: liberating the mind is a prerequisite for liberating the land.

Despite the devastation, there remains hope for rebuilding a new Syria. But it will require a courageous confrontation with the past: holding those responsible for torture and killing accountable, and healing the sectarian wounds deeply embedded in Syrian consciousness. Reconstruction will not only be a physical endeavor but a long and arduous journey to rediscover the Syrian spirit that the regime sought to crush and dissolve.

Let us envision a day when Syria finds its way to true freedom—not merely the absence of tyrants but the presence of dignity, citizenship, and humanity. Only then will there be no “House of My Aunt” or “Behind the Sun”—only a homeland where rights are equal and humanity thrives. Only then can we talk about Syrians’ resistance to occupation, when Syrians have restored their collective consciousness as a united people that is capable of reclaiming stolen Golan Heights and ending their occupation. For now, Syrians must unite, move past their differences, embrace social justice and freedom of expression, and focus on rebuilding their nation, securing their borders, and resisting all forms of aggression while reconstructing both the people and the homeland.

Happy for the Moment, so Anxious About the Future

by Jamal Saeed

I was arrested three times. The first time, I stayed in prison for about eleven years. Three times I was a prisoner of conscience, but never was a sentence issued against me. No matter how old my memory gets, I will never forget the moments of my arrest, and I will never forget my release — especially the first time.

On the day I was called to be released, I was washing my clothes in a blue plastic basin. I was not sure if they would release me or move me to another prison. While I was detained in Tadmur Prison and then in Saidnaya Military Prison, I dreamt that a day would come when the crowds would storm the prison and release us (we were about 12,000 prisoners in Tadmur and about 2,000 prisoners in Saidnaya). This miracle happened to other prisoners just a few days ago, and I was able to watch it on the news.

I will never forget the day I left Syria, about ten years ago. The country has become, for me, all this: memories, pictures, news, and videos that I see on the screen in front of me 10,000 kilometres away. I will never forget the pictures of the prisoners leaving Saidnaya Prison two days ago. For just one moment, I wanted to hug the prisoners one by one, and to embrace the air, trees, soil, and stones of Syria. On the screen in front of me, I waited to see if I knew any of the prisoners waiting to be released. Among them: Abdul Aziz Al-Khair, Iyas Ayash, Maher Al-Tahhan, Khalil Ma’touq, Jihad Muhammad, Faiq Al-Mir, Ali Al-Shihabi, Raja’a al-Naser, Zaki Kordillo and his son Mahyar, Adel Barazi, and Adnan Hamoudi. But no one appeared and none of their names were mentioned in the lists prepared by volunteers (these lists included the names of released prisoners). I wished to meet all the prisoners and ask them about these friends of mine. I still send messages via Messenger and WhatsApp to people I only know in the virtual world, and I ask about the aforementioned prisoners. So far, I have not received a positive answer.

I am very happy that Syria got rid of the military dictator. I felt on hearing this news, if only briefly, that I was no longer a person but the country itself — one that had finally been freed of its nightmare.

On the other hand, I am very concerned about the nature of the armed militias that have taken control of cities from Idleb and Aleppo in the north to Damascus, Daraa, and As -Suwayda in the south. The regime fell as a result of the struggle of many Syrians — especially during the past fourteen years. That struggle involved the killing, arrest or expulsion of many Syrians who believed in a modern state in which we are equal citizens regardless of religion, race, color or gender. All those years witnessed the weakening of secular forces and organizations, and the killing or arrest of many believers in pluralism — whether by the regime or by ISIS or by Jabhat al-Nusra. The latter (which changed its name to Hayat Tahrir al-Sham) led the last battle that was able — due to local, regional and international circumstances — to overthrow the dictatorial regime.

I will not hide my fears about this type of militia, as I do not trust that this form of political force is capable of building a modern state of law or a secular democratic state. I hope I am wrong. Among the reasons for my lack of trust is that Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham arrested and killed Syrian activists and journalists (including Raed Fares and Hamoud Junaid) who were against the dictator. I will not forget the secular activists of Kafranbel whom Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham paralyzed — by constantly harassing and threatening them. I am still waiting for the release of the prisoners languishing in prisons this organization built in Idleb.

A new horizon has opened for two contradictory possibilities. I hope that freedoms will replace military tyranny and not give way to yet another tyranny under a religious umbrella — as happened in Iran after the return of Khomeini.

No matter how old my memory gets, I will never forget the fall of the dictator. May every dictator face the same fate.

Anxious Freedom

by Dr. Hamza Rastanawi

My grandfather waited for the fall of Hafez al-Assad’s dictatorship. Sadly, he passed away in 1974, and the dictator remained in power.

My father, too, spent his life waiting for the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime. Unfortunately, he passed away in 2016, and the dictator still clung to his throne.

I, too, have waited for what feels like an eternity for the dictator’s fall—dreaming of this moment. In reality, I long ago despaired of ever seeing it.

Then, suddenly, three days ago, the dictator fell. He fled like a rat to Russia. I am now 50 years old, and paradoxically, the moment I have waited for so long brings me no happiness.

The fear that shadowed me since childhood is gone. I searched but could not find it. Instead, I feel lost, adrift in the absence of that ever-present fear. Perhaps these are the withdrawal symptoms of fear—anxiety over the newfound freedom! However, that anxiety has begun to subside.

The day before yesterday, I saw a 26-year-old woman who had been released from Assad’s prison. She was holding the hand of a three-year-old boy she had given birth to while in captivity. She does not even know who his father is.

Yesterday, I watched an interview with Ragheed Tartari, a pilot who had spent 43 years in Assad’s prisons, making him the world’s longest-serving political prisoner. Arrested in 1981 for refusing to bomb civilians in Hama, he endured decades of unimaginable hardship. Yet, even in his cell, he created tiny sculptures and works of art using olive seeds, breadcrumbs, and sugar.

Art conquered the dictator. I believe in the power of art and in the unbreakable spirit of the Syrian people.