Advocacy & Aid

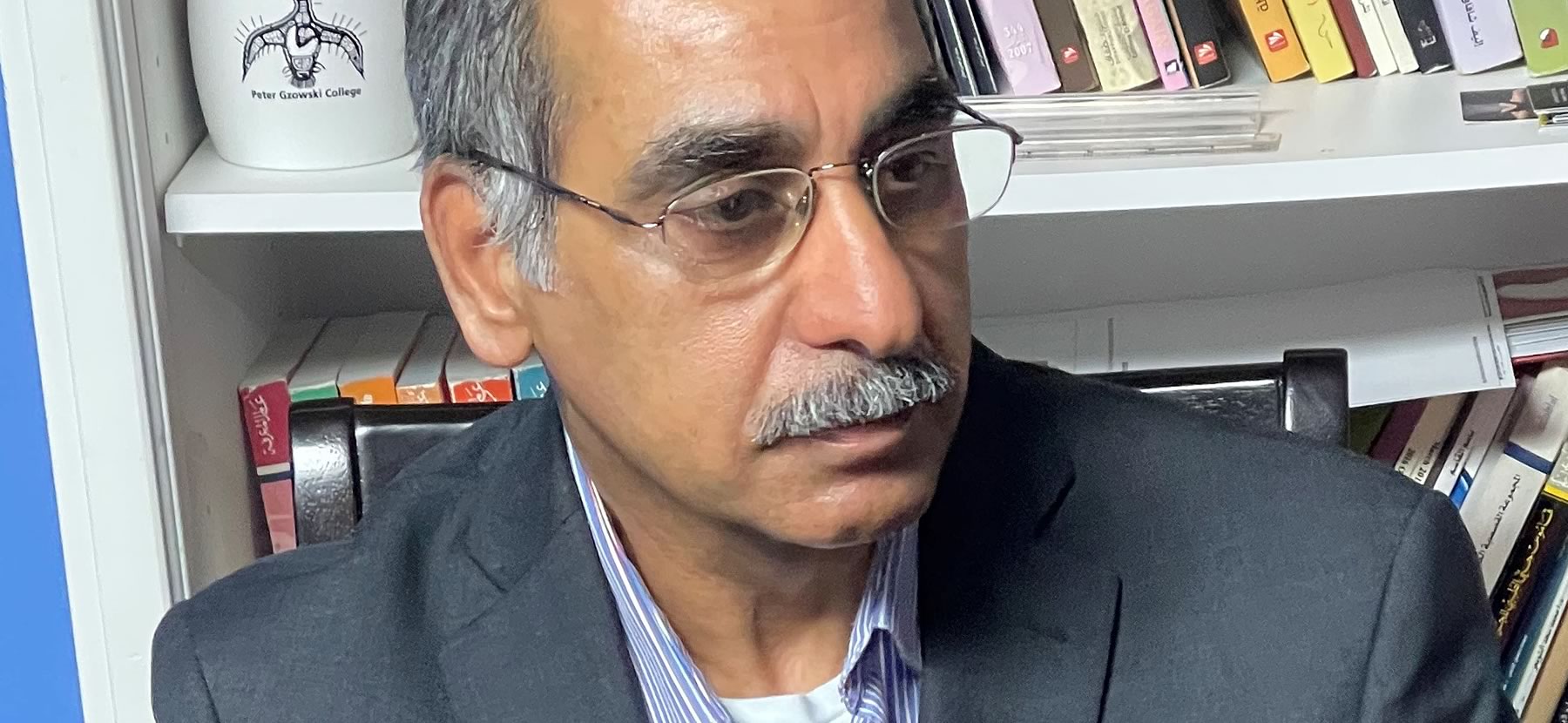

Abdulrahman Matar is a Syrian-born writer, journalist, poet and novelist. He is a member of PEN Canada’s Writers in Exile group, the Syrian writers’ Association, and the Writers’ Union of Canada. He came to Ontario as a refugee in 2015. Matar is the founder and director of the Mediterranean Studies Center and Syrian-Mediterranean Cultural Forum – SEEGULL. He has published five books and is a researcher in Euro-Mediterranean relations and human rights, and an activist for civil society issues. As a result of his writings, he has been arrested five times and spent nearly 10 years in prison. His novel “Wild Mirage” is about his experiences as a prisoner of conscience. Matar was interviewed by PEN’s Student Intern, Sara Taslim.

Abdulrahman Matar is a Syrian-born writer, journalist, poet and novelist. He is a member of PEN Canada’s Writers in Exile group, the Syrian writers’ Association, and the Writers’ Union of Canada. He came to Ontario as a refugee in 2015. Matar is the founder and director of the Mediterranean Studies Center and Syrian-Mediterranean Cultural Forum – SEEGULL. He has published five books and is a researcher in Euro-Mediterranean relations and human rights, and an activist for civil society issues. As a result of his writings, he has been arrested five times and spent nearly 10 years in prison. His novel “Wild Mirage” is about his experiences as a prisoner of conscience. Matar was interviewed by PEN’s Student Intern, Sara Taslim.

PEN Canada: Once a month, PEN Canada’s Writers in Exile group gathers at Toronto’s Romero House for Refugees to meet other members and share stories. Has this experience helped you to find a home in Canada? How does it help others with a similar story to yours?

Abdulrahman Matar: It is very important to me and other members of the Writers in Exile group. We don’t just tell stories in these meetings; they open a wide window for me into Canadian society, especially the community of authors, journalists, and freedom of expression activists. Through the group, I have come to know the world around me and have met many beautiful people. We have stories in common — about writing, being detained and arrested, and the asylum process in Canada, and in other parts of the world where we hope to eventually obtain refuge and protection.

I consider some people in the group members of my extended family. I’ve accepted support from them that few writers in exile receive, namely the translation of my novel into English — a new addition to the group’s projects and plans. Since joining PEN Canada I’ve attended the monthly meeting quite often and I’m truly proud of the friends I have made. Many writers in exile have received important assistance from the Writer-in-Residence post at George Brown College and the Humber College Scholarship. These programs are important for us and I have applied for both several times, as I desperately needed them. However, I did not receive either. English proficiency is an important part of the application and maybe my story, or project, did not convince the admissions committee.

PC: The Toronto Multicultural Festival gave you its annual Empowering Communities Prize for your role in research and human rights advocacy, and your writing and poetry. How do you balance such a busy schedule?

AM: The award conferred great responsibilities upon me but also presented great opportunities. It helped me to continue working for ideas I believe in, and towards strengthening the relationship between refugees and their new society. Writers, journalists, and cultural activists have a great responsibility to work on the process of integration, preserve cultural identity, respect everyone’s culture and languages, and encourage dialogue and cooperation. The award is also helping me to defend rights and freedoms in my country of origin, and in other parts of the world where repressive governments hold sway. But my time is limited. Like many other newcomers and refugees, I work in a factory. This is a far cry from my primary profession as a writer and a journalist, but freedom of expression and cultural activism are so important to me that I remain committed to them.

PC: In 2019, the Syrian Mediterranean Cultural Forum hosted the “Arab Voices” poetry program in Aurora, Ontario, at which many Arab writers and artists, including yourself, performed. What did you hope the audience would take away from the festival?

AM: Arab culture is an important part of Canada’s multicultural and multiethnic society. It is as rich, authentic, and ancient as any other culture, but Arab creators and voices are still little known in most circles. I established the Forum in 2013, during my stay in Istanbul, and brought it with me to Canada. It links Arab writers with other Canadian authors and helps to raise their profiles. With few available translations, this is not an easy task. Our events are an attempt to introduce Arab creators to Canadian audiences. That is why we call the program “Arab Voices”. We scheduled events at the University of Toronto, in public libraries, and at the Old City Hall in Newmarket; but the pandemic stopped all of that. We have important authors, poets, novelists, dramatists, musicians, and journalists here in Canada and we want Canadians to hear our stories and learn about our struggles for freedom.

PC: Your novel “Wild Mirage” describes the hardships you have endured: years of political imprisonment, oppression, and abuse. How have those influenced your work as a writer and activist?

AM: These are extraordinary, bitter, and cruel experiences — ones that are hard to describe. Even a writer cannot convey the amount of pain and oppression that a detainee endures, or the feeling of being a fugitive or refugee. But these hardships also sent me down a different path. I wrote a novel about political imprisonment and then I was arrested twice because I fought for freedom and democracy. I have written a lot about that and feel the need to write more. I want to write more so that I can recover from the experiences of being arrested and seeking asylum.

I often feel overwhelmed by what I have lived through. We must write to be liberated from the effects of torture, for the sake of those still in detention, and for the sake of freedom. Yet, the more I write about that period, the more I feel the pain.

I still suffer from anxiety and claustrophobia — especially at work. I worry about specific appointments such as our scheduled downtime, and I dislike the uniforms we wear, and the ringing bells that announce work breaks or the start and end of the working day.

A change of place and engagement with a community can help you to heal. Canada is a country of freedom, where I feel I am gradually recovering my lost humanity. There are still severe impacts, but I will overcome them. It has taken a long time, through constant writing, even about the details, to rid myself of the fear and pain that were growing inside me like a tree.

PC: As founder and director of the Mediterranean Studies Center & Syrian-Mediterranean Cultural Forum you have created spaces for different cultures to meet and for artists to share their stories and identities. Do you believe this also shares the voices of those who do not yet have the freedom to speak up?

AM: Freedom of expression is our main concern. We don’t just talk about it, we really do it. In these spaces, freedom of expression has no limits. Write and read whatever you want. We are also interested in the voices of writers and journalists who have been deprived of their rights and freedoms. We fight for them, and we pass on their stories and news so that the world knows about them. We read their poems and recall their memories in events related to political, cultural, and literary dialogue.

PC: What books and authors, Arabic or non- Arabic, do you feel capture the duality of artistic cultural expression and humanitarian freedoms?

AM: This question deserves special attention and I cannot answer it hurriedly. I do not wish to simply list writers who have studied how culture is related to rights and freedoms, but one important writer is the Palestinian-American writer and critic Edward Said who raised questions of human rights and freedoms through literary criticism and research into cultural and political phenomena especially in the relationship between the West and the East.

PC: What are you currently reading that you would recommend?

AM: I am reading an Arabic novel and the poetry of Nobel laureate Louise Gluck (“A Burning Wheel Passes Over Us”) translated into Arabic. Recent events in Palestine have also prompted me to reread Edward Said and the poems of Mahmoud Darwish. Their books are available in Arabic and English. Both are very important authors and I’d recommend them even though I don’t like to press a book, author, or belief on a reader.

PC: As a Syrian writer and journalist, a member of PEN Canada, a member of the Syrian Writers Association, and the Writers Union of Canada, your story is an inspiration to many. How did you stay motivated to keep fighting? What advice do you have for those facing similar difficulties?

AM: I have faced many hardships including arrest, prosecution, and deliberate marginalization. I have suffered at the hands of a dictatorship and those of a militant Islamic and terrorist group. I have paid a huge price for my freedom and so has my family. I have experienced displacement and asylum in several countries before finally settling in Canada peacefully. I did so because I believe it is worth striving for freedom and human rights, especially freedom of expression. I believe that writers and journalists must defend these rights and freedoms. I’d like to express my gratitude and appreciation to all the friends and family members who have offered me their unwavering support throughout my ordeals.

Subscribe for updates about PEN Canada’s work to defend free expression.